TOPEKA, Kan. (AP) — Retiree and public employee groups in Kansas are contemplating a lawsuit against a law enacted this year that would force teachers and government workers to make concessions on their pensions to address the state retirement system's long-term funding problems.

The law would force most employees covered by the Kansas Public Employees Retirement System to choose between paying a higher percentage of their salaries toward their pensions and having their future benefits reduced. Workers hired after June 2009 wouldn't face higher contributions, but they'd be required to choose one of two alternatives for cutting their benefits.

Many state officials have long assumed that past Kansas Supreme Court rulings prevent the state from going too far in cutting future retirement benefits. But KPERS projects a $7.7 billion shortfall between its anticipated revenues and the benefits promised to workers through 2033, and this year's changes would help close that gap.

Recommended For You

The retiree and public employee groups already have consulted with attorneys, said Jane Carter, executive director of the Kansas Organization of State Employees, which is part of a coalition on pension issues, Keeping the Kansas Promise.

"I think that is something that we will address as a group and figure out where to go," she said.

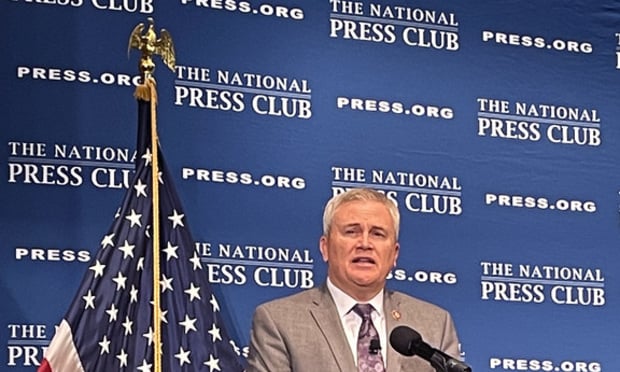

Leaders of the Republican-controlled Legislature have anticipated that retiree and public employee groups might file a lawsuit over the KPERS changes. House Speaker Mike O'Neal, a Hutchinson Republican and an attorney, compared the threat of a legal challenge to the threat facing any major project inspiring heated debate.

"When you build a power plant, you expect somebody to file suit," O'Neal said. "Every side has the right to have those legal issues evaluated."

The new law, signed last week by Republican Gov. Sam Brownback, puts part of the burden of closing the long-term pension shortfall on taxpayers by increasing the state's annual contribution to KPERS, starting in July 2013. Over four years, it phases in a $95 million increase, according to KPERS and legislative researchers.

The measure also establishes a study commission to examine whether the state should start a 401(k)-style plan for new public employees. Such a plan would tie retirement benefits to investment earnings, rather than guaranteeing benefits based on a worker's years of experience and career-end salary, as KPERS plans now do.

Retiree and public employee groups and Democratic legislators supported the increase in the state's contributions to KPERS, viewing it as the state catching up after shorting its payments for years. They are wary of the study commission, but saw it as far preferable to a plan from House GOP leaders to start a 401(k)-style plan for workers hired after June 2013.

The coalition also has misgivings about changes coming for KPERS participants.

About 131,500 teachers and government workers covered by KPERS pay 4 percent of their salaries to the pension fund. Under the new law, they'd be given the choice next year of increasing their contributions to 6 percent by 2015, with a small bump in future benefits. If they didn't take that option, their future benefits would be cut significantly.

An additional 20,000 employees hired after June 2009 already pay 6 percent of their salaries into KPERS, and they've been promised annual cost-of-living adjustments in their benefits after they retire. Under the new law, they could either give up the adjustments or keep the adjustment but have their base benefits cut.

Because KPERS is governed by federal Internal Revenue Service rules, the IRS must sign off on those choices. If the IRS doesn't, then workers hired before July 2009 will pay more toward their pensions and get a bump in benefits, and the other workers will lose their future cost-of-living adjustments.

Asked about the possibility of a lawsuit, Carter said, "A lot of us are waiting to see what the commission is going to do and to see the IRS ruling."

The most-often cited Kansas Supreme Court decision on public pensions is from a 1980 case in which Topeka police officers and firefighters challenged a law increasing their payments to KPERS.

The court struck down the increased contribution. It declared that public pensions represent a contract between employer and worker, and public employees acquire an interest in their retirement benefits that "cannot be whisked away by the stroke of a legislative or executive pen."

O'Neal and Senate President Steve Morris, a Hugoton Republican, said the state can defend this year's law by noting past adjustments for KPERS that benefited workers, such as changes in the formula for calculating benefits or one-time bonus checks or cost-of-living adjustments.

O'Neal said the pension system's long-term financial problems would be a key legal issue.

"Certainly, moving forward, where there is a compelling interest in making the system sustainable for future employees, that is a consideration that I don't think the court would ignore," O'Neal said.

Still, Morris acknowledged some doubts, particularly because workers hired after June 2009 would see their benefits reduced, no matter what choice they made.

"We're dealing with unknowns here," he said.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.