Recently, my wife went to the doctor with stomach issues. The doctor recommended a simple diagnostic test called a HIDA scan. We have an HSA high-deductible health insurance plan with a $6,450 deductible, meaning we would be paying for the procedure out-of-pocket until our deductible was met.

Recently, my wife went to the doctor with stomach issues. The doctor recommended a simple diagnostic test called a HIDA scan. We have an HSA high-deductible health insurance plan with a $6,450 deductible, meaning we would be paying for the procedure out-of-pocket until our deductible was met.

Before my wife left the doctor's office, she asked the receptionist what she thought was a simple question: “How much is this going to cost?”

The receptionist had no idea — and she had no way to check. She looked at my wife like it was an unreasonable question. A manager contacted a third-party billing agency to get her a quote, which ended up being nothing close to what we actually paid in the end.

Economic models assume participants have perfect information. In reality, they often have no information whatsoever.

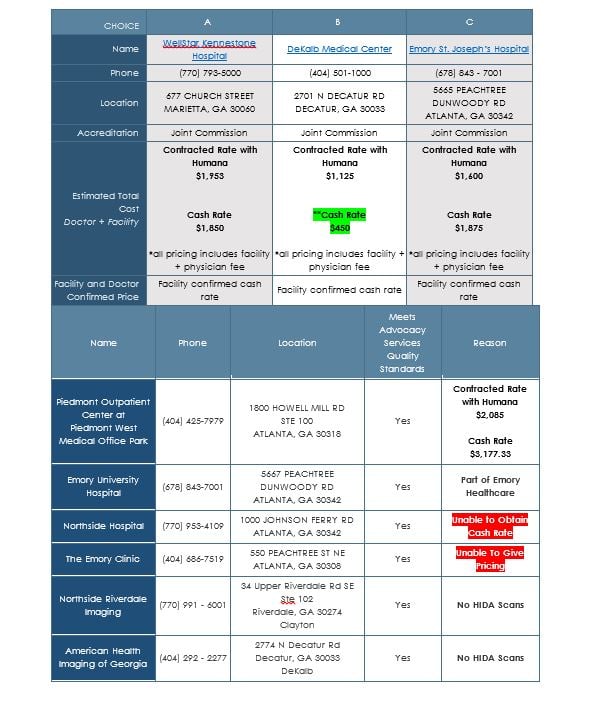

Because I am a population health manager, i.e., employee benefits consultant, so I have access to transparency solutions that aren't readily available to the average consumer. See the findings below:

There are several observations that are noteworthy:

- If I had done this research myself, I would still be obtaining this data

- Our secret weapon supplied this data in less than 24 hours

- Insurance contracted prices/rates ranged all over the map, from $1,125 to $2,085

- Cash rate was higher than the insurance prices with Emory and Piedmont?

- How can this be? Can this be right?

- Pricing could not be obtained from the Emory Clinic

- Why? Do they not need business? Do they not want to compete?

- Cash rate could not be obtained from Northside Hospital

- Why? Is this a complicated request?

- The best price was $450 at DeKalb Medical Center, which is where we went.

I also researched pricing at nationally renowned Healthcare Bluebook, which provides free online tools designed to enable consumers to understand the fair price they should pay for health care services in a certain area. It came up with a price of $798.

I thought this was a glaring example of how screwy health care pricing is, but I had no idea.

A permanent pacemaker implant at Pennsylvania's Phoenixville Hospital is billed at $211,534. Four hours away at Unitown Hospital, the same procedure costs $19,747, or 91 percent less. Over 160 hospitals across the country charge at least $100,000 for a pacemaker, while 46 charge less than $30,000.

The official bill rate to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, at Bayonne Hospital Center in New Jersey, is $99,690. At Lake Whitney Hospital in Texas, it's $3,134, or 97 percent less. Thirty-five hospitals bill an average of more than $50,000 to treat COPD, while 161 bill less than $7,500.

A kidney and urinary tract infection faces a $132,569 bill at Crozer Chester Medical Center in Pennsylvania, but $6,224 at Wyoming County Community Hospital.

Those are just a few examples I pulled out of a massive database released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in April 2015. The group spilled the beans on what 3,000 hospitals charge for 100 of the most common medical procedures. It then compares those “chargemaster” prices to what Medicare actually paid for the treatments, based on hospital-specific estimates of the treatment's cost, including administrative overhead.

The database — which contains nearly 1 million data points and crashed my computer three times — has two screaming-in-your-face takeaways.

The first is the difference between bill rates among hospitals. It's just huge. At least a dozen treatments I looked up have a difference between the high-cost and low-cost provider of more than ten-fold, and several treatments will cost more than 20 times as much, depending on what hospital you're in.

The report doesn't contain perhaps the most important metric: outcomes and quality of procedures performed. Teaching hospitals and hospitals that receive an influx of seriously ill patient transfers from other hospitals will also have higher-than-average costs.

But even looking at average prices by state shows massive discrepancies. In California, the average hospital charges $101,844 to treat respiratory infections, while Maryland hospitals bill an average of $18,144, or 82 percent less. New Jersey hospitals bill an average for $72,084 for “simple pneumonia,” while Massachusetts hospitals charge an average of $20,722.

The second takeaway is that the gap between what hospitals charge for procedures and what Medicare actually pays for those procedures is off the charts. Of the 100 procedures tracked in the database, the average difference between “average charges” and “average payments” is — I'm not making this up — 72 percent.

Related: Jury deems Centura Health $230K surgical bill 'unreasonable,' awards $766

Go back to my pacemaker example above. Phoenixville Hospital may charge $211,534 for a pacemaker implant, but Medicare pays the hospital $17,835 for the procedure. Unitown Hospital bills $19,747 for the treatment, and is reimbursed $15,281. What starts out as a five-fold price discrepancy shrinks to a 14 percent difference in the end.

Steven Brill, a journalist who wrote an eye-opening cover story for TIME in February 2013 (the longest article in the history of TIME) exposing discrepancies in health care bill prices that paved the way for the data's release, wrote:

The hospital lobby, led by the American Hospital Association, is going to howl that publication of these chargemaster prices is unfair. Only a minority of patients are actually asked to pay those amounts, it will argue. Insurance companies, which cover the majority of patients, receive huge discounts off the list prices, though they pay substantially more than Medicare does.

True, but that doesn't settle the matter. It actually highlights some of the deepest problems. Those “minority of patients” are no small group; they're the estimated 48 million Americans without health insurance. For medical providers to say that chargemaster prices don't reflect the true cost of care is to admit that some of the most financially vulnerable Americans may be being billed absurdly inflated prices. It's ironic, but some of the greatest benefits to having health insurance aren't necessarily the insurance coverage, but the price-negotiating power that insurance companies strike with care providers. At least that is what they tell you. But as we have seen with my wife, the insurance companies aren't delivering as advertised; getting a 50 percent discount off the chargemaster price of an item that costs $13 and lists for $199.50 is still no bargain. In our research, cash was the least expensive as well as the most expensive — truly a box of chocolates.

Imagine a banana in a supermarket. It costs $1 for those paying with Visa, $3 for those paying with MasterCard, and $32 for those paying with cash. You can't sign up for Visa until you're 65, and you can only get a MasterCard if you have a nice employer or a decent income. Worse, customers have no idea that such price discrepancy exists. They don't even know how much they'll pay for the banana until long after they've eaten it.

That would be absurd. No one would put up with it.

“There is no such thing as a legitimate price for anything in health care, prices are made up depending on who the payer is. So, the fact that different prices are paid by different payers is not what makes health care different — not in the slightest. What makes it different is that the payer is not the consumer, but the payer is the employer, the government, or an insurer.” George Halvorson, former chariman of Kaiser Permanente

But it's how our health care system works.

It appears that our crazy system of hospital prices (and the inefficiency that accompanies it) is not natural or inevitable. Instead, what we have appears to be the product of a system in which someone other than the patient pays the bill.

Where else in America is the person utilizing the services not paying for 100 percent of what they are purchasing? As I like to say, the purchase of medical goods and services by employer health plans resembles no other business transaction in American commerce.

An employer must embrace our simple solution to this problem, which is to move toward paying for medical goods and services in the same manner that the corporation buys everything else — with transparency and with upfront knowledge of the cost. We firmly believe that unless employers put their claims costs back in the box using this proprietary strategy that cracks the code, they will never move the needle in reducing their claims cost.

About the Author: Carl C. Schuessler, DHP, DIA, GBDS is the managing principal of Mitigate Partners, who provide risk management, cost containment and employee benefits consulting services. By serving as a fiduciary and steward of clients' health plan dollars, and focusing on how to reduce the cost of healthcare (rather than the cost of insurance), they operate as population health managers rather than as “brokers.” They created and trademarked FairCo$t, a health plan that incorporates the ideas and the high performance health care solutions their journey uncovered.

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.