While some employees want to quit their jobs to take care of their kids, most who have quit to focus on caregiving said they did so because getting paid help was too expensive. (Photo: Shutterstock)

While some employees want to quit their jobs to take care of their kids, most who have quit to focus on caregiving said they did so because getting paid help was too expensive. (Photo: Shutterstock)

Employees say that taking care of kids negatively affects their work performance. But most bosses appear oblivious to the problem.

That's the main takeaway from a report authored by two Harvard Business School researchers, based on a survey of 301 HR leaders and 1,547 employees.

More than half of the HR leaders polled said that their organization has not tried to measure the impact of caregiving on their workforce. And only 24 percent said they believed that caregiving “influenced workers' performance.”

Related: Caregiving benefits moving to forefront

Asked what types of behaviors associated with caregiving tend to impede employees' career progression, 33 percent of HR leaders cited missed days of work, 28 percent cited tardiness and 17 percent cited leaving work early.

Meanwhile, 80 percent of workers said that caregiving did affect their productivity.

The loss of workers due to child-rearing alone clearly has a major impact on the U.S. workforce. Roughly half of employees aged 26 to 35 say they have left a job due to caregiving duties. So have more than a quarter of employees under 26.

While some employees want to quit their jobs to take care of their kids, most who have quit to focus on caregiving (53 percent) said they did so because getting paid help was too expensive. Forty-four percent said that they were unable to find “trustworthy” care for their loved ones and 40 percent said that they were unable to balance work and caregiving responsibilities.

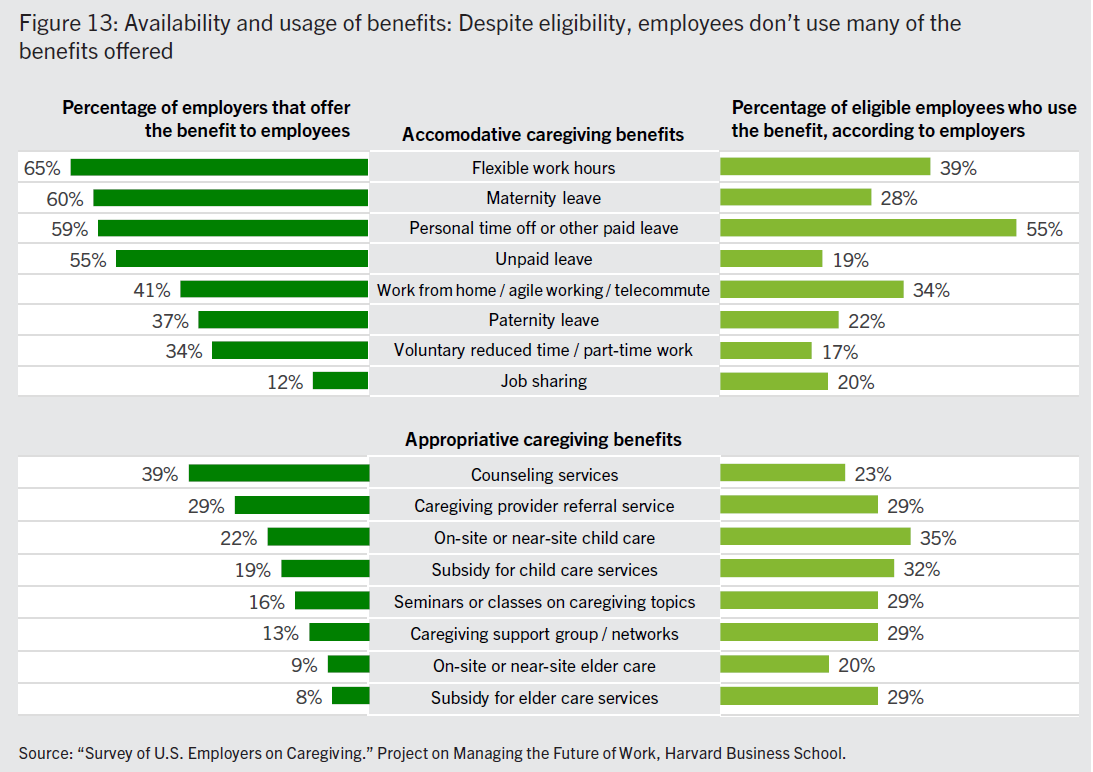

The report suggests that organizations redesign benefits to relieve caregiving stress for middle or lower-wage workers. Traditionally, the report notes, the best-paid employees also have the most generous benefits aimed at caregiving. The problem is, those employees may be the ones who are least in need, since they have an easier time paying for childcare.

“Setting benefits based on organizational level may not reflect today's skills marketplace—certain middle-skills jobs are extraordinarily hard to fill, even though the associated compensation is similar to that received by workers in easier-to-fill positions,” said the report.

The study authors also recommended closer collaboration between private employers and local governments to better understand the needs of the regional workforce.

While the report noted that the U.S. remains the only industrialized nation that does not provide workers any guarantee to paid parental leave, it cautioned employers not to wait until there is a government intervention on the matter:

“The stakes are too high for employers to await the type of broad-based mandates federal legislation is likely to yield. Smart employers will seize the opportunity to gain an advantage in the increasingly ferocious war to recruit and retain talent through a deliberate strategy to become a corporate care leader.”

Read more:

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.