Along with alcoholism and suicide, opioids are part of the so-called deaths of despair phenomenon that has helped increase white American mortality rates since the turn of the century. (Photo: Getty Images)

Along with alcoholism and suicide, opioids are part of the so-called deaths of despair phenomenon that has helped increase white American mortality rates since the turn of the century. (Photo: Getty Images)

America's opioid crisis is a terrible tragedy in itself. Increasingly, though, the evidence suggests that it's behind another malaise: the growing ranks of prime-aged males dropping out of the labor force.

The epidemic of opioid and opiate drug abuse contrasts sharply with a broader improvement in Americans' health. Violent crime, domestic violence and teen pregnancy are all way down. Cancer survival rates are up, and HIV is on the way out. Air and water pollution have decreased.

Related: Opioids now kill more people than cars do

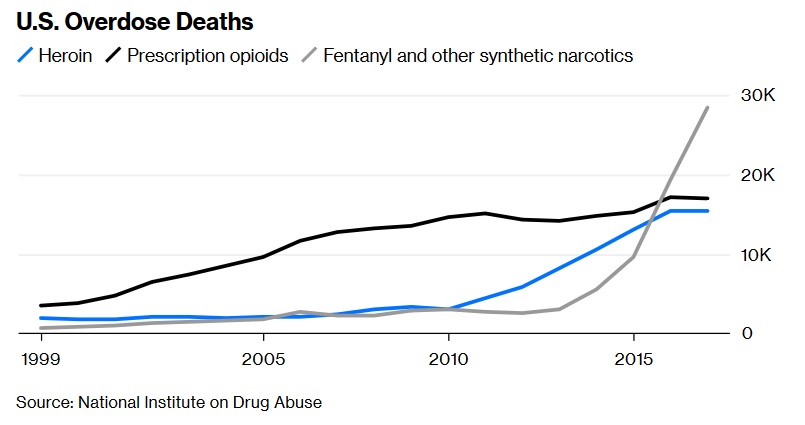

The trouble started in the early 1990s, with a boom in the prescription of opioid painkillers like oxycodone and hydrocodone. Then worries about rising addiction rates led doctors to cut patients off, which often sent them looking for street drugs like heroin instead. By the time prescriptions peaked in 2011, it was too late. A culture of addiction spread, supply networks developed, and powerful synthetic opioids like fentanyl became the top killers:

The main cost is counted in lives. Opioids now kill more Americans than car accidents or guns. Along with alcoholism and suicide (which may itself be partly driven by opioid addiction), opioids are part of the so-called deaths of despair phenomenon that has helped increase white American mortality rates since the turn of the century. And the epidemic is quickly spreading to African-Americans as well.

That said, the crisis also has economic costs. There's of course the enormous expense of treating addicts. But opioids also burden the U.S. by taking workers out of the productive economy.

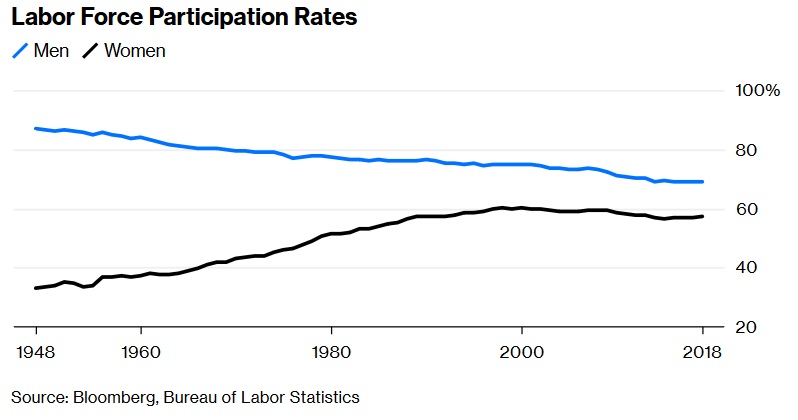

Men's participation in the labor force has been declining for many years, but that trend seems to have accelerated since the turn of the century. Meanwhile, women's participation, which had been rising for decades, plateaued in the late 1990s and has declined since 2009:

Much of the decline is due to educated people taking early retirement, or to people staying in school longer as education becomes more important. But a sizeable chunk may be due to drug problems, especially among men.

In 2017, Princeton University economist Alan Krueger noted a correlation between pain medication use and being out of the labor force. In the early 2010s, he found, 43.5 percent of men aged 25-54 who were out of the labor force reported using pain medication the previous day. For those who were employed or actively looking for the work, the number was only around 20 percent. Krueger also found that labor force participation had fallen more in counties where opioids were prescribed more heavily, even after controlling for a number of other local conditions.

But as Krueger noted, causality is hard to determine. It might be that people started using drugs because they were disabled or had no chance of finding a job, rather than the reverse. A new paper from economists Dionissi Aliprantis, Kyle Fee, and Mark Schweitzer at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland attempts to disentangle cause from effect.

The researchers reason that if lack of a job causes opioid use, then areas hit harder by the Great Recession should have seen larger increases. Using a common indicator of labor market conditions, they didn't find a relationship. This suggests that drug use is driving people to drop out of the labor force, not vice versa.

This paper isn't conclusive. First of all, the authors' measure of temporary changes in labor demand could have statistical problems that make it unreliable for this sort of measurement. Second, the effect of weak labor markets on drug use might be longer term — people who think they'll be unemployed only briefly might not turn to drugs, while people who see no prospects might start using heroin or fentanyl. Although the authors try to control for long-term labor market conditions, there's always the chance they've missed something.

Nonetheless, evidence is piling up that the opioid epidemic is eroding the foundations of the U.S. economy by impairing the labor force. It's a problem that policymakers need to address urgently.

Although President Donald Trump has declared the epidemic a national emergency, he hasn't done much to address it. For one, he should stop trying to cut Medicaid benefits, which help addicts receive needed treatment. Government health insurance should be expanded, not shrunk. Legalizing marijuana at the federal level would help, too — legalization has been found to lower opioid use.

It will be a generation before the impact of the horrendous opioid epidemic fades from the national statistics. But with the right steps now, the U.S. might at least be able to end it more quickly.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith ([email protected])is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion. To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Whitehouse at [email protected]

Read more:

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.