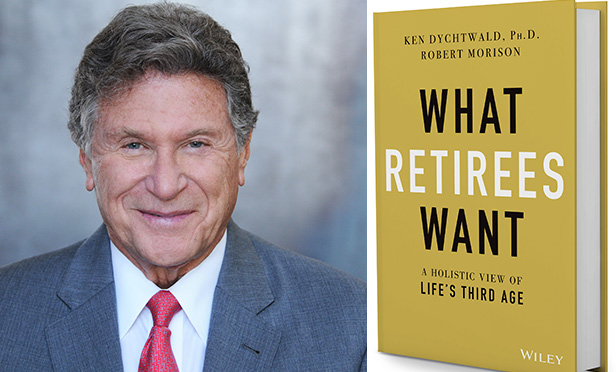

Ken Dychtwald and his new book.

Ken Dychtwald and his new book.

The coronavirus pandemic is a shocking "intervention" whose biggest impact will show up in retirement planning: The crisis has forced older people to consider the importance of matching health span to life span and think about aspiring to a more streamlined lifestyle, argues Ken Dychtwald, founder and CEO of Age Wave.

The "Pitchman for the Graying Revolution," as Fortune Magazine dubbed him, psychologist and gerontologist co-founded Age Wave in 1986 to help companies and government develop strategies to serve the fast-growing aging population.

In the interview, Dychtwald, 70, discusses why only a small portion of retirees — most of them in a quandary over financial planning — have financial advisors.

For one, he says, there's the question of trustworthiness, which needs to be "resolved."

Author of 17 books, the Ph.D., who has devoted nearly a half-century to the field of gerontology, has a new one due on July 15: "What Retirees Want: A Holistic View of Life's Third Age," co-written with Robert Morison (Wiley). It represents the authors' three decades of research on gerontology and retirement.

In the interview, Dychtwald, whose clients include Allianz, Ameriprise, Bank of America, Charles Schwab, Edward Jones and Merrill Lynch, stresses the need for older men and women to become adept at digital technology both for socializing and medical care, the latter made clear by the pandemic's lockdown-prompted telemedicine visits.

Dychtwald co-founded Age Wave with wife Maddy Dychtwald upon perceiving that the approaching "age wave," based largely on the trend of increasing longevity, would shift the focus from younger consumers to the needs of baby boomers and the generation that preceded them.

BenefitsPRO's sister site ThinkAdvisor recently interviewed Dychtwald, a fellow of the World Economic Forum, speaking by phone from Orinda, California, where his firm is based. The Newark, New Jersey, native lamented retirees' lack of financial literacy and opined that the majority of financial books were of little practical help: "Most people don't want to get a Ph.D. in economics," he said. "They want to know what they should do when making financial decisions."

Here are highlights of our conversation:

THINKADVISOR: How has the pandemic impacted the longevity revolution?

KEN DYCHTWALD: It was an intervention. For the first time in our lives, or maybe ever, everyone in the world was given a near-death experience. Out of the blue a few months ago, everyone was having discussions or thinking about, "What if I die? What if somebody I love dies?" Now they're giving a lot more thought to what really matters: the essentials for living a good life, a more streamlined life.

Please elaborate.

The pandemic isn't just about being sick or losing money. It's about the psychological impact of: What happens if I can't earn money or if my kids lose their jobs? We've all been given an opportunity to stop and think about what's really important. For older people, it means paring down to what matters most.

Has the pandemic changed planning for and expectations about retirement?

The pandemic has had the biggest impact on what we used to think of as retirement because now all the pieces on the table are moving around. It's brought to light the importance of matching health span to life span. People are thinking more and more about the importance of health and what they can do to optimize it.

In your upcoming book "What Retirees Want: A Holistic View of Life's Third Age," you cite a study in which 8 in 10 retirees said they were willing to seek professional financial advice about retirement planning — but in fact only half as many work with advisors. Overall, only 26% of Americans have a financial advisor, you write. Why the disconnect?

A few reasons. Some people feel they're not rich enough to have an advisor. They got that feeling from advertising years ago, which [gave them the impression] that only fancy people have financial advisors. Another reason is that some consumers don't know who to trust, that maybe financial firms aren't really concerned about their best interest but just about making money for themselves. That trustworthy theme has got to be resolved.

What other reasons are there for failing to hire an advisor?

Many people don't like the idea of being scrutinized about how they spend their money or why they may not have saved enough. Or they don't want to be "looked down on" because they're heading into their retirement years and haven't prepared. That's unnerving and embarrassing for them.

Let's return to your argument that "the trustworthy theme" needs to be resolved. By whom?

By everyone. The movement of the last few years toward fiduciary responsibility was a step in the right direction. But part of the collateral effect of [Sen.] Bernie Sanders [running for president] and even [President] Trump saying that Wall Street people don't care about you and are only interested in making themselves richer is that a lot of people don't know if anyone [in the industry] really cares or will look them in the eye and try to give them a helping hand.

How valid is that perception?

A lot of financial services firms want to do the right thing — it's not as though there's some evil empire. But I don't think they've done such a wonderful job of marketing and communicating their intents. People often mistakenly assume they don't [qualify] to have a financial advisor; so they just stay on the path [of going it alone]. That may not be in their best interest.

You point out in your book that most Americans aren't "financially fluent." Certainly financial jargon can be a turnoff to the average consumer, right?

Not only a turnoff — it could be Martian language, for all I know. I sit in the back of the room at financial meetings where I'm a speaker and hear people talking about "hedge" this and "403(b)" that and "529." I have no idea what they're talking about! It's the U.S. government as well.

What do you mean?

My Medicare statements say on the top left, "This is not a bill," but on the top right they say, "This is your bill." Fifty million people are getting these incomprehensible statements every month.

Why isn't something done to correct this unintentional obfuscation?

There hasn't been a public willingness to say, "Hey, I don't know what you're talking about. Why don't you make this user-friendly and understandable, and cut the crap!" That goes not only for financial firms but for the government, too.

How much responsibility should pre-retirees take to learn just what funding they'll need during their so-called golden years?

There are a lot of people who are, kind of, willfully in denial of taking this seriously, even though they feel they're drowning [in incomprehension]. One study found that 80% of the American public said they've never sat down and tried to figure out how much money they'll need to last through retirement and how much they have to save. [For a start], they don't understand Social Security.

Why are people so lacking in financial literacy?

Most have never been taught the basics of saving and finance. The Medicare and Social Security systems aren't user-friendly. There's a need for holistic financial education and guidance. People don't know who to trust and talk to about making financial decisions.

What can you suggest to ameliorate the situation when it comes to retirement planning?

We need a financial version of Google Maps or Waze navigation that would navigate a route to where you want to go in retirement with the least possible problems.

Anything else that the pandemic has brought into sharper focus?

The idea that we've allowed older people to fall on the unhappy side of the digital divide, which isn't good for anyone. Of people in America over 75, only 62% use the internet and only 28% use or feel comfortable connecting with social media, according to Pew Research. That's dangerous.

Why?

Because now it's about life and death. Four months ago it was a kind of joke to say that grandma and grandpa weren't so good at email or didn't know how to use Facebook or Instagram. But it's the responsibility of older men and women to enable themselves to be excellent with technology for both socializing and the delivery of medical care. It's essential that they're fluent, even talented, with technology.

In your book, you argue that "ageist" marketing practices are "hurting business" in general. In what way?

Including people over 50, [older consumers] are a group of 100 million representing 70% of all the worth in America. So to be paying less attention to older men and women because you've got a preference for the youth market is unwise. It's not a smart business decision.

READ MORE:

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.